From the...:

David Dunn: Excerpt from Gradients (1999)

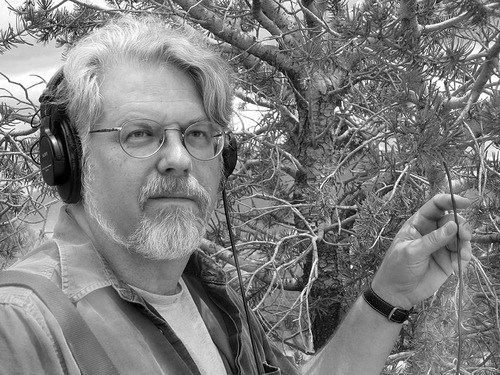

From the album Autonomous and Dynamical SystemsBorn in 1953 in San Diego, California, David Dunn is an American composer whose music has explored the domains of environmental performance, field recording, and electronic sound synthesis. Working at the boundaries of contemporary experimental practice, Dunn has devoted his career to overcoming what he calls “music’s insufficiency as a discipline.” Making modern composition relevant, according to Dunn, means embracing the formative possibilities of new sound technologies, integrating the findings of post-Newtonian science, and approaching creative activity from a position of ecological awareness.

Dunn’s teachers include Harry Partch, with whom he worked from 1970 to 1974, and Kenneth Gaburo, to whom Dunn dedicated his beautiful 1993 composition “…with zitterings of flight released.” Although his own work explores avenues far from the mainstream of electronic music, Dunn is well versed in its history. His 1992 pamphlet “Die Eigenwelt der Apparate-Welt (Pioneers of Electronic Art)”—now 20 years old—is still an excellent overview of the technological and aesthetic developments of the genre’s first hundred years.

In the year 2000, Dunn founded the Art and Science Laboratory in Sante Fe, New Mexico, an organization devoted to (among other things) “electronic arts history and practice, post-cinematic aesthetics, robotics and haptics, sound art, chaos and nonlinear dynamics, bioacoustics, and environmental conservation and education.” Through these various activities Dunn pursues the vision of an integrated, post-disciplinary union of knowledge and practice whose purpose is, in his words, “to creatively put forth alternatives to the existing order.”

Though he acknowledges the ubiquitous influence of John Cage, Dunn also draws a sharp distinction between his own work and much of the post-1950 experimental tradition. Following the logic of Cage’s radical reconception of music, Dunn presses the question, “What is the meaning of sound-making activities if they are not traditional music and are not intended to be?” His answer is that music (and art more broadly) cultivates the discipline and focused engagement required to reorient ourselves to the spiritual and ecological realities of the 21st century. Music is a kind of survival training for the existential crisis of late modernity.

Dunn’s music can be broken up into three broad categories: site-specific works intended for outdoor performance; electroacoustic works using field recordings; and “pure” electronic works based on mathematical models.Music is not just something we do to amuse ourselves. It is a different way of thinking about the world, a way to remind ourselves of a prior wholeness when the mind of the forest was not something out there, separate in the world, but something of which we were an intrinsic part. Perhaps music is a conservation strategy for keeping something alive that we now need to make more conscious, a way of making sense of the world from which we might refashion our relationship with nonhuman living systems.

In his environmental performance works, Dunn orchestrates interactions of human beings, machines, and the natural environment in order to musically invoke the “spirit of place” (genius loci) of particular locations. In Entrainments 2 (1985), three performers record stream-of-consciousness descriptions of the environment from three peaks in the Cuyamaca Mountains of California. These recordings are played back over loudspeakers during the performance, along with drones based on the astrological charts for the current time and location. In addition, ambient sounds are gathered, processed, and fed back into the mix by a parabolic microphone carried by a performer walking slowing around the perimeter of the performance space. A very different approach to site-specific environmental music is found in Mimus Polyglottos (1976), in which Dunn uses synthetically generated tones to initiate a musical “conversation” with a group of mockingbirds. (To hear the piece, check out my related post at Data Garden.)

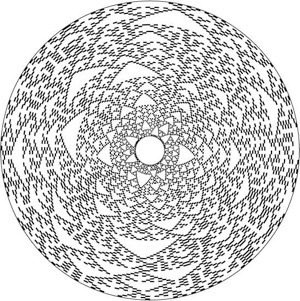

Image from Dunn and Crutchfield’s Theater of Pattern Formation

With regard to field recording, Dunn has nothing but scorn for “preservationist” soundscapes that purport to capture the untainted sounds of nature. His own works in this genre, though based largely on unedited recordings, acknowledges his role in framing the acoustic image. Field recordings don’t so much capture the sounds of nature itself as they project our perception into what Gregory Bateson called the “fabric of mind” that connects all of reality. Recording is a human intervention; like composition it is a “strategy for expanding the boundary of reality itself.”

Dunn’s best known work in this vein, Chaos and the Emergent Mind of the Pond (1991), weaves together a number of field recordings made beneath the surface of North American and African freshwater ponds. The resulting composition is aptly described as “aquatic jazz…a dance between periodicity and chaotic swirl.” In the rich and highly complex rhythmic interactions of the underwater fauna, Dunn hears something more than the merely instinctual signals of senseless organisms. He imagines the insectoid orchestra as a collective expression of a profound sentience residing in the supposedly lowest forms of animal being. “The sounds of living things are not just a resource for manipulation,” Dunn writes, “they are evidence of mind in nature and are patterns of communication with which we share a common bond and meaning.”

More recently, Dunn released The Sound of Light in Trees (2006), an album-length composition based on recordings of beetles inside conifer trees in northern New Mexico. The beetles’ activities, inaudible to the naked ear and even to conventional microphones, are picked up by specially built “vibration transducers” inserted underneath the trees’ bark.

Apparently disconnected from his sonic investigations of the natural world, Dunn has also created several distinctive works of “pure electronics.” Here too, however, his goal is the same: to render in sound the immanent forces of dynamic systems. In all his activities, Dunn isn’t “composing” in the traditional sense, but trying to unleash latent energies and trace their trajectories as expressions of a cosmic order hidden just beneath the surface of everyday experience.

Lorenz (2005), a collaboration between Dunn and scientist James Crutchfield, spins out a dizzying cascade of sound by creating feedback loops between computer-generated chaos equations and a custom-designed audio interface. In another piece, Nine Strange Attractors (2006), Dunn follows similar procedures to explore the peculiar sonic behavior of various mathematical entities with names such as Owl, Pendulum, Rossler, and Van der Pol. As Warren Burt suggests, this piece can be seen as a modern spin on the classical genre of theme and variations, with each attractor offering a different “perspective” on the underlying sound-generation matrix.

Gradients (1999) was created using a computer program to convert the lines of computer graphics into shimmering fields of sine waves. The piece consists of three sections of equal length, each palindromic in structure and possessing elements of formal self-similarity as well. Dunn emphasizes that these works are not simply inspired by fashionable notions of chaos theory, but rather incorporate these mathematical entities into their structure. Computer models of mathematical formulas allow us to artificially recreate the complexity already existent in nature: the networks of sounding digits become self-regulating systems, chaotically ordered in the sense of the ancient Greek word kosmos.

No comments:

Post a Comment